Anorexia vs. ARFID: Do You Know the Critical Variances?

Eating and feeding disorders, including anorexia nervosa (AN) and Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID), are alarmingly prevalent within the neurodivergent community, particularly among Autistic females. Interestingly, the incidence of anorexia in females could signal undiagnosed autism, a phenomenon noted by Zucker et al. (2007). Complicating matters, anorexia and ARFID can co-exist or be mistaken for each other, complicating their treatment and support. This challenge is compounded by their shared characteristics: restrictive eating patterns, the risk of nutritional deficiencies, and weight loss.

However, it's crucial to understand their differences. ARFID, commonly observed in Autistic and ADHD populations, is not just about the food's quantity but its variety and sensory attributes, which, if overlooked, can hinder recovery from eating disorders. This article aims to shed light on these distinctions, emphasizing the importance of tailored approaches in managing these complex feeding conditions.

Contents:

What is the difference between Anorexia and ARFID?

According to the DSM-5, Anorexia Nervosa (AN) is defined as a serious mental health condition characterized by:

A significantly low body weight

An intense fear of gaining weight or becoming fat or a distorted perception of body weight or shape.

Having a distorted view of your body size or shape, where self-worth is too tied to these views, or not recognizing how serious being underweight is.

The current understanding of anorexia is both outdated and carries stigmatizing undertones. It falls short in acknowledging the multifaceted influence of neurodivergence. Let's consider a few essential adjustments needed for a more inclusive and accurate perception of anorexia:

Expanding the Perspective on BMI: The prevailing emphasis on being "underweight" neglects people with anorexia who maintain a "normal" or even higher BMI. This oversight can result in numerous individuals suffering in silence, their struggles dismissed due to not fitting the conventional physical stereotype.

Reassessing the Fear of Gaining Weight: Although the intense fear of gaining weight is recognized as a symptom, it's not a universal experience. For many neurodivergent individuals, anorexia may stem from a search for safety and control in a world largely designed for neurotypical experiences. Characteristics frequently seen in autism and ADHD, such as a preference for routine, challenges with change, and an intense focus on specific interests, may morph into a harmful obsession with food and exercise, ultimately contributing to anorexia.

Reimagining the Narrative of Distorted Body Image: The prevailing image of anorexia often involves a thin girl looking in the mirror perceiving herself as overweight. However, this does not resonate with everyone's experience. For numerous neurodivergent people, the motivation behind their eating and exercise routines is not to change their weight or body shape. Rather, it is influenced by traits associated with autism and ADHD, such as categorizing foods as "healthy" and "unhealthy," or developing rigid routines around eating and exercise.

Regrettably, the current diagnostic criteria in the DSM for anorexia overlooks those whose underlying motivations extend beyond body image concerns, and fails to represent individuals across all body types. It particularly misses the mark for neurodivergent individuals, where Autistic and ADHD traits frequently underpin their relationship with food and exercise, diverging from a focus on altering one’s weight or shape. Another critical area deserving closer examination, yet frequently overlooked, involves the intersection of neurodivergence, eating disorders, and gender identity.

Eating disorders and neurodivergence are much more prevalent among the LGBTQIA+ community. People identifying as transgender (trans) or non-binary possess a gender identity that does not align with the sex assigned to them at birth, which can contribute to a strong desire to change one’s appearance. Weight and shape can play a major role in the experience of body dysphoria, which is another important factor to consider when labeling someone with anorexia.

Regardless of the varying (and if we’re being honest, infinite) contributing factors of anorexia nervosa, below symptoms are ubiquitous across individuals with the condition.

Desire to lose weight

Obsession with weight and food

Distorted body image (not always)

Obsession with exercise (not always)

Hyperfocus on numbers (calories, steps, portion sizes, etc)

Strict rules and routines around food

What is ARFID?

In contrast to anorexia, which is classified as a mental health illness rooted in a need for control, ARFID presents differently. Anorexia involves strict rules and routines around food, exercise, and body metrics. Conversely, the DSM-5 categorizes ARFID as a feeding or eating disorder characterized by a persistent disturbance in eating or feeding behaviors. Naureen Hunani, RD, suggests that ARFID can be understood as a form of feeding disability.

This perspective arises from the idea that feeding differences create significant challenges in a world lacking accommodation. Essentially, the lack of support for these differences can itself be disabling. Viewing ARFID through this lens encourages a broader understanding of eating disorders, recognizing them not solely as mental health issues but also as potential forms of neurodivergence that require societal accommodation.

This disturbance can result in significant weight loss, nutritional deficiency, dependence on enteral feeding or oral nutritional supplements, and marked interference in psychosocial functioning.

In general, ARFID is understood to differ from anorexia, bulimia, and other “typical” restrictive eating disorders in that the eating difficulties are not rooted in a desire for thinness, but rather driven by other factors – factors such as sensory sensitivities, fear of negative consequences, or a lack of interest in eating.

Types of ARFID

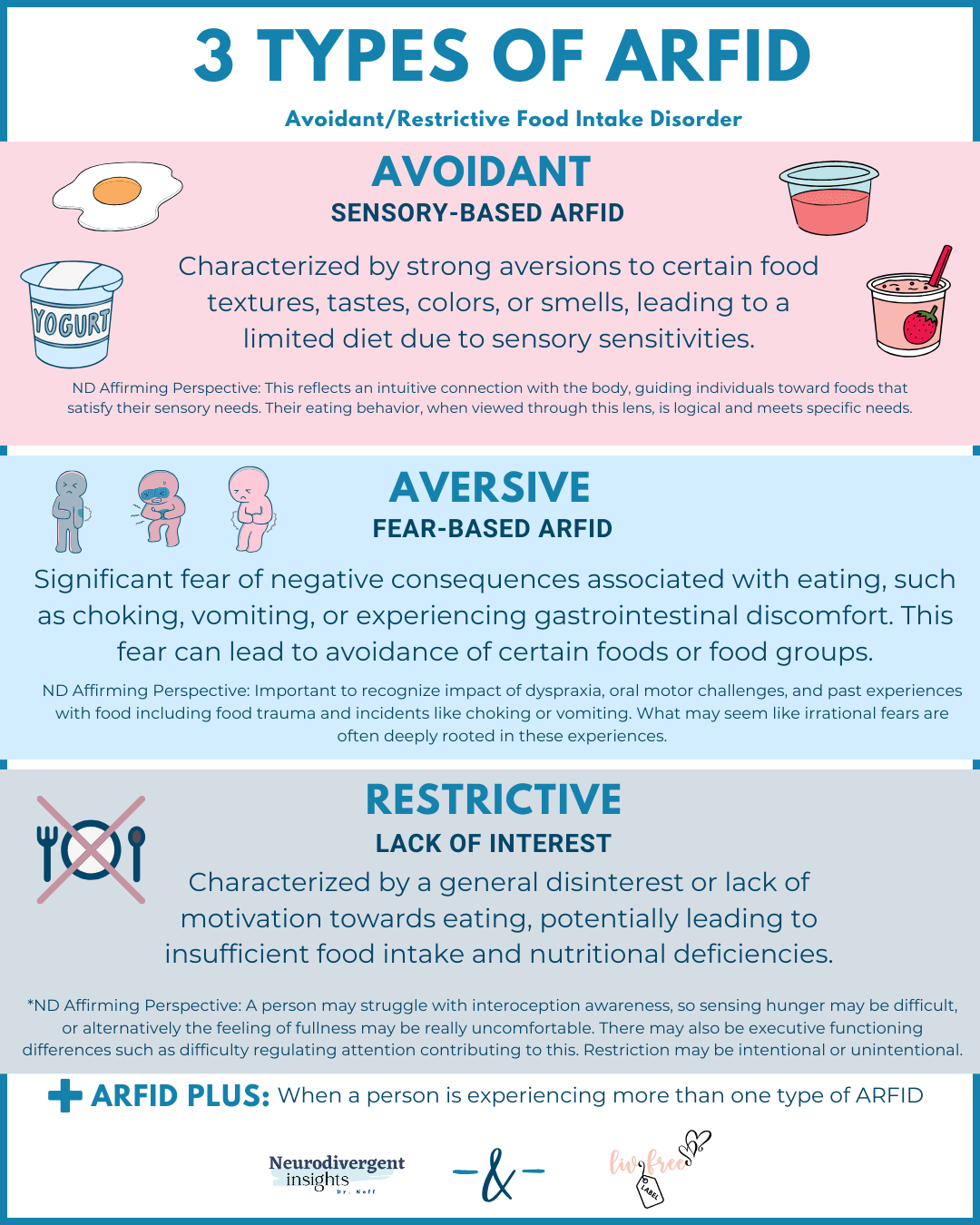

These factors form the foundation of the three ARFID subtypes:

1. Sensory-Based ARFID: Individuals with this presentation may have strong aversions to certain textures, tastes, colors, or smells of foods. They may find it challenging to tolerate a wide variety of foods due to sensory sensitivities.

ND Affirming Lens: This may reflect an intuitive connection with the body, guiding individuals toward foods that satisfy their sensory needs. Their eating behavior, when viewed through this lens, is logical and meets specific needs (Hunani, 2024).

2. Fear-Based ARFID: Some individuals with ARFID may have a significant fear of negative consequences associated with eating, such as choking, vomiting, or experiencing gastrointestinal discomfort. This fear can lead to avoidance of certain foods or food groups.

ND Affirming Lens: It’s important to note that this fear may be based on actual past experiences and complicated by motor challenges or incidents of choking or vomiting (Hunani, 2024).

3. Lack of Interest ARFID: This subtype is characterized by a general disinterest or lack of motivation towards eating, potentially leading to insufficient food intake and nutritional deficiencies. Unlike other forms, individuals with this subtype don't necessarily have strong aversions or fears concerning specific foods. Instead, they may lack the desire or appetite to eat, often due to diminished interoceptive awareness, meaning they might not recognize or respond to their body's hunger signals.

ND Affirming Lens: A person may struggle with interoceptive awareness, so sensing hunger may be difficult, or alternatively the feeling of fullness may be really uncomfortable. There may also be executive functioning differences such as difficulty regulating attention contributing to this. Restriction may be intentional or unintentional (Hunani, 2024).

*ARFID Plus is another subtype when a person falls in more than one type of ARFID and begin to develop other difficulties. Many people with ARFID fall into this ARFID plus category.

Due to the strong overlap of ARFID traits and autistic traits, there is some debate in the ARFID community about whether it’s truly a “disorder” or merely an eating difficulty as a result of the Autistic experience. After all, isn’t fear of negative consequences quite an impressive adaptation if you’ve had traumatic food encounters in the past? Nonetheless, ARFID can be incredibly debilitating as it dramatically restricts your ability to have a peaceful relationship with food, and we appreciate the perspective of Naureen Hunani, RD, who conceptualizes ARFID as an eating disability.

Overlap Between ARFID and Anorexia

It goes without saying that both anorexia and ARFID pose challenges to all aspects of an individual’s wellbeing. Not only will people affected by one or both disorders experience nutritional deficiencies, gastrointestinal issues, and weight loss as a result of their limited diet, but they tend to live in constant fear and anxiety. Here is a breakdown of some of the ways anorexia and ARFID overlap:

Potential for weight loss and nutritional deficiencies, though the underlying motivations differ.

Gastrointestinal discomfort, which can be both a cause and effect of the disorders.

Challenges with eating in social settings, though often for different reasons: anxiety about food itself in ARFID vs. anxiety about perceived judgment or losing control in AN.

Both may involve a limited variety of accepted foods, but for different reasons: sensory issues in ARFID vs. calorie control in AN.

Differences in interoceptive awareness, affecting perception of hunger and fullness in unique ways.

Fear of food-related consequences for sure, but also fear of judgment from others. The avoidance of criticism (not to mention the compound effect of judgment of neurodivergent traits) often leads to difficulty eating around others, if at all.

Both can lead to body mistrust and dissociation from body or alternatively hypervigilance of body.

How to Support Someone With Both:

How can you best support someone with anorexia and/or ARFID? While everyone is unique and will therefore have different support preferences, two words are universally important: trust and safety.

Any type of eating disorder is rooted in a lack of trust and safety, which may be the core reason for why feeding and eating difficulties are so common among neurodivergent people in the first place. There is no treatment that magically cures eating disorders…it’s all about creating an environment safe enough for an individual to trust that they can do the work necessary to heal. So instead of asking how to best support someone with an eating disorder, let’s ask: how can I create more safety and trust?

Future Resources

To learn more about atypical presentations of anorexia and undiagnosed autism check out Rainbow Girl by Livia Sara where she walks through her journey of misattuned eating disorder treatment and her ultimate recovery.

You can learn more through Liv’s website where she has several free resources as well as offering coaching and courses. You can also check out her podcast interview where she discusses ARFID with Lauren Sharifi, a registered dietitian.

RDs for Neurodiversity provides several trainings for providers, as well as have some great educational resources and blog posts for neurodivergent people.

Neurodivergence, Feeding Differences and ARFID Spring 2024 (this course offers 15 CPEUs for dietitians hosted by Naureen Hunani). Starts May 1, 2024

About Livia Sara

Livia Sara is an autism advocate and eating disorder survivor that now helps others overcome their own mental barriers through her courses, coaching programs, and books. She is the creator behind the blog livlabelfree.com and the host of the Liv Label Free Podcast. Livia is a lifelong learner that loves listening to audiobooks, going on walks, and reading the latest science on all things neurodiversity and eating disorders! Learn more about working with Livia HERE.

References:

Khalsa SS, Craske MG, Li W, Vangala S, Strober M, Feusner JD. Altered interoceptive awareness in anorexia nervosa: Effects of meal anticipation, consumption and bodily arousal. Int J Eat Disord. 2015 Nov;48(7):889-97. doi: 10.1002/eat.22387. Epub 2015 Feb 24. PMID: 25712775; PMCID: PMC4898968.

Mahler, K., & Hunani, N. (2024). An Affirming Approach to Supporting Interoception, Feeding Challenges & ARFID [Course]. Presenter(s) Kelly Mahler and Naureen Hunani. Kelly Mahler.com.

Zucker, N. L., Losh, M., Bulik, C. M., LaBar, K. S., Piven, J., & Pelphrey, K. A. (2007). Anorexia nervosa and autism spectrum disorders: guided investigation of social cognitive endophenotypes. Psychological bulletin, 133(6), 976.