Dorsal Vagal Shutdown: How to Identify a Shutdown

Affiliate Disclaimer: This article contains affiliate links, which means receive a commission if you click a link and purchase something that we have recommended. Please note that clicking these links won’t cost you any extra money, but they help us keep this site up and running. Thank you for your support!

Do you ever find yourself battling chronic fatigue, persistent depression, migraines, or a sense of disconnection from life? If so, you're not alone. These symptoms can stem from various sources, but one concept that might offer some insight is the idea of Dorsal Vagal Shutdown—a term rooted in Polyvagal Theory.

Before we dive deeper, it's important to note that while Polyvagal Theory is influential, it remains a topic of ongoing research and debate within the scientific community. In this article, we will explore the concept of Dorsal Vagal Shutdown through the lens of Polyvagal Theory, while also grounding the discussion in broader, well-established neuroscience for a more comprehensive understanding.

You may be wondering, "What exactly is Dorsal Vagal Shutdown?" While the concept of "freezing" in response to a crisis is widely recognized, there's less awareness about the prolonged states of withdrawal and disconnection that can occur. This phenomenon is sometimes referred to as Dorsal Vagal Shutdown, but within the broader scientific community, it is more commonly described as hypoarousal, tonic immobility, or the freeze response—all characterized by a significant withdrawal from interaction with the external world.

This nervous system response can be triggered by trauma but can also result from sensory overload, leading to what some might call a sensory shutdown. Understanding this concept is particularly important for neurodivergent individuals, who may be more prone to these experiences.

In this article, we'll explore Dorsal Vagal Shutdown, including its mechanisms, the differences between acute and chronic shutdown, and how to identify and support someone experiencing it. Along the way, we’ll integrate broader scientific perspectives to support a well-rounded discussion.

What is Dorsal Vagal Shutdown?

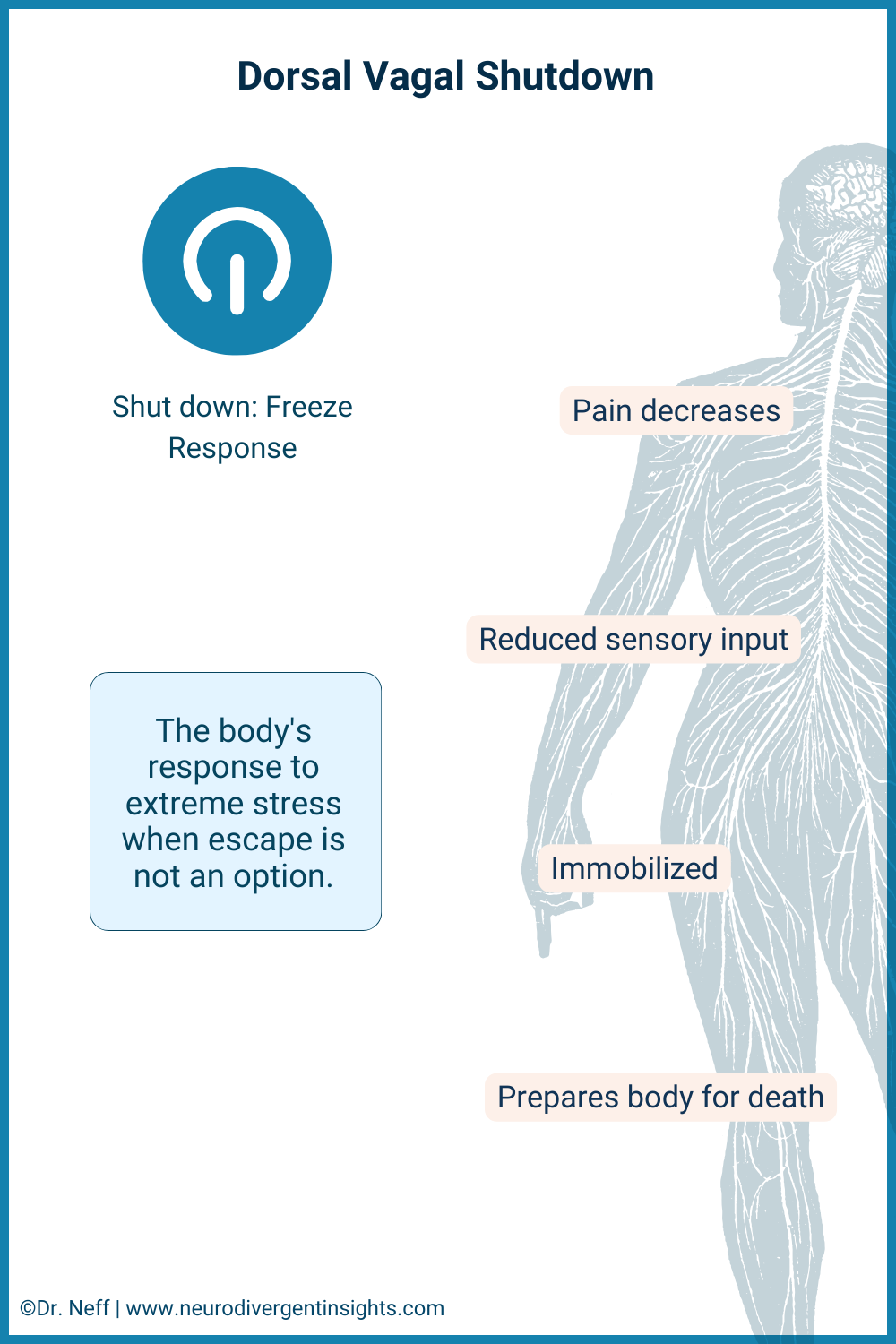

Dorsal Vagal Shutdown can be thought of as the body’s natural way of hitting the pause button when faced with extreme stress or trauma. In this state, everything slows down internally to conserve energy—it's like dimming the lights and lowering the volume in response to overwhelming conditions. According to Polyvagal Theory, this response is managed by the dorsal branch of the vagus nerve, which can trigger what's often referred to as a "freeze" state.

Although Dorsal Vagal Shutdown is a specific concept within Polyvagal Theory, the broader phenomenon of hypoarousal is widely recognized in neurobiology. Hypoarousal refers to a state where the nervous system downregulates its activity in response to overwhelming stress or trauma, leading to symptoms such as fatigue, dissociation, and emotional numbness.

In this mode, the body shifts its priorities to protection, reducing pain signals and lowering both mobility and arousal levels—as if bracing for a situation from which there is no escape. This response can make us feel extremely tired, numb, or disconnected from the world around us and even from our own emotions. Essentially, it's the body’s way of shielding itself during overwhelming situations.

For neurodivergent individuals, particularly those who are Autistic, understanding this type of shutdown is crucial. Research suggests that, compared to non-autistic individuals, autistic people may be more prone to experiencing a shutdown response to stress rather than the typical fight-or-flight reaction. This can sometimes manifest as an outward appearance of calmness, which may mask significant internal disconnection and immobility. Recognizing this distinction is important, as it highlights the profound, though often invisible, ways that stress impacts neurodivergent individuals. To explore more about the neurodivergent nervous system and its unique responses, you can read further here.

The Parasympathetic Nervous System

Understanding Dorsal Vagal Shutdown requires a closer look at the role of the Parasympathetic Nervous System (PNS). As a crucial branch of the Autonomic Nervous System, the PNS is primarily responsible for our "rest and digest" functions, acting as a counterbalance to the Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS), which governs the "fight-or-flight" response.

However, during overwhelming stress, the body can enter what is known as a mixed state, where both the SNS and PNS are active. In this state, the SNS may initially prepare the body for action, but when escape or confrontation is not possible, the PNS steps in to conserve energy. This mixed state can lead to a shutdown response, manifesting as fatigue, dissociation, or even blackouts in extreme cases.

For Autistic individuals, this response is particularly significant, as variations in sensory processing and emotional regulation can amplify shutdown states. This may present outwardly as calmness, but it often masks a deep internal disconnection and immobility.

The Vagus Nerve

The vagus nerve, which stretches from the brainstem down to the abdomen and influences the heart, lungs, and digestive system, plays a crucial role in our body’s autonomic functions. Acting as a vital communication link, it oversees essential processes such as speech, heartbeat regulation, and digestion.

Central to the Parasympathetic Nervous System (PNS), the vagus nerve helps the body return to a state of calm following moments of stress or danger.

While Polyvagal Theory highlights the dual nature of the vagus nerve—where one branch promotes social connectivity and relaxation (ventral vagal), and the other can trigger a protective "freeze" response in the face of severe stress (dorsal vagal)—it’s important to understand that the vagus nerve’s role is multifaceted and extends beyond just these responses. The vagus nerve is also crucial for regulating digestion, heart rate, and immune function, among other vital processes.

One critique of Polyvagal Theory is that it oversimplifies the role of the vagus nerve by focusing primarily on its involvement in social behavior and stress responses. In reality, the vagus nerve influences a wide array of bodily functions, and its role cannot be fully captured by a single theoretical framework.

According to Polyvagal Theory, in extreme cases of stress, the dorsal (back) branch of the vagus nerve can initiate a shutdown response, leading to a state of immobilization or numbness. However, outside of Polyvagal Theory, this shutdown is often explained as a state of hypoarousal or dissociation. Experts in broader neurobiology describe this as the body’s way of conserving energy when it perceives an inescapable threat. This response results in a mixed state where both the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems are involved.

Vagal Tone

A closely related concept is vagal tone. While it might not be a household term, vagal tone plays a significant role in our health and emotional well-being. It is a key measure of the health and flexibility of the vagus nerve and has a substantial impact on overall well-being.

Vagal tone is typically measured through heart rate variability (HRV), which assesses the variation in time between each heartbeat. A higher HRV generally indicates a healthy, flexible vagus nerve, capable of efficiently regulating stress responses. Conversely, lower HRV can signal reduced vagal tone, which may increase susceptibility to stress and anxiety.

High vagal tone is associated with better emotional and physical health, including lower blood pressure and improved immune function. On the other hand, low vagal tone may make individuals more susceptible to physical health issues, stress, and anxiety, and can affect recovery from physical or emotional challenges.

Enhancing vagal tone through practices such as mindful breathing, laughter, engaging in creative activities, and enjoying pleasurable movement can support better stress management and resilience. This is especially beneficial for Autistic and ADHD individuals, who may more frequently experience reduced vagal tone and flexibility. Additionally, tools like the Sensate, device, the Safe and Sound Protocol, or a TENS unit with ear clips can also help stimulate the vagus nerve.

Interested in learning more about how vagal tone is assessed? You can explore the link between heart rate variability and vagal tone here.

Hypoarousal or Dorsal Vagal Shutdown?

Let’s explore the concept of hypoarousal, which is widely recognized in the fields of neuroscience and psychology. Imagine our nervous system like a car’s engine that can run at different speeds. Ideally, the engine runs smoothly, balancing acceleration (the sympathetic branch) and deceleration (the parasympathetic branch) to handle whatever road we’re on.

When we face a stressful situation, it’s sometimes like pressing the gas pedal too hard, revving the engine into overdrive—this is called hyperarousal, where we might feel anxious or panicky. Other times, our system does the opposite and slams on the brakes. This is known as hypoarousal, where overall alertness and energy drop.

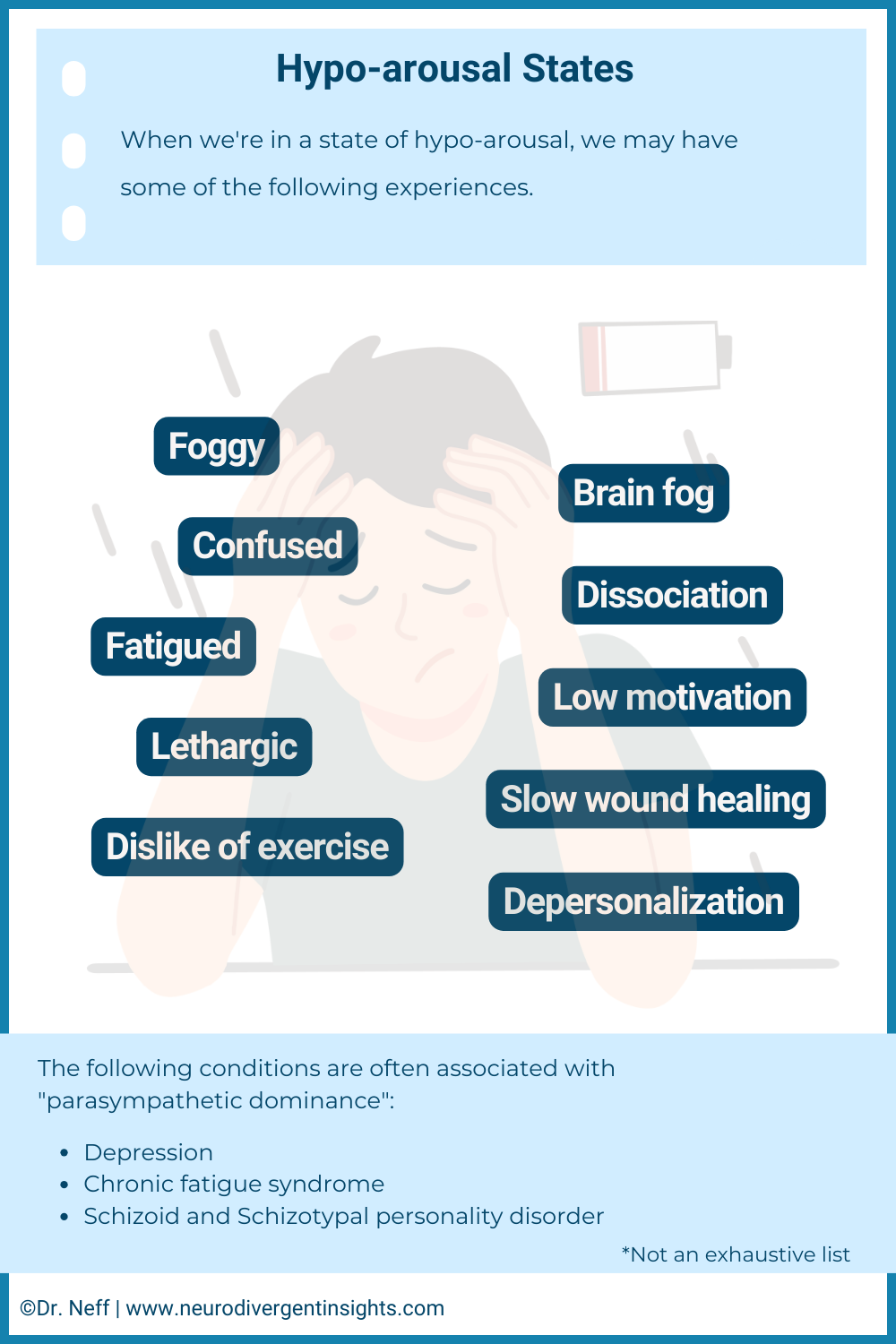

Hypoarousal is characterized by a general reduction in nervous system activity, which can manifest in various forms, including physical immobilization, cognitive fog, and emotional withdrawal. In broader neurobiology, hypoarousal is understood as a state where the body and mind slow down significantly, leading to feelings of numbness, detachment, or even physical collapse. Mental health conditions like depression, schizoid or schizotypal personality disorder, and dissociative disorders are often associated with hypoarousal. In contrast, conditions like anxiety and OCD are more linked to hyperarousal, characterized by heightened alertness.

Within the framework of Polyvagal Theory, hypoarousal is described as Dorsal Vagal Shutdown. According to this theory, the dorsal (back) branch of the vagus nerve initiates a protective "freeze" response in the face of severe stress, conserving energy and protecting the body when it perceives an inescapable threat.

Understanding hypoarousal, and its interpretation as Dorsal Vagal Shutdown within Polyvagal Theory, sheds light on the profound ways our bodies protect us during overwhelming stress.

Why a Dorsal Vagal Shutdown Happens

According to Polyvagal Theory, Dorsal Vagal Shutdown serves as the body’s emergency "freeze" response in the face of overwhelming stress or trauma, when the usual "fight or flight" reactions are not viable options. This protective mechanism conserves energy by minimizing metabolic activity and reducing visibility to potential threats—a response managed by the dorsal vagal complex. It’s a primal survival strategy that temporarily puts the body into a state of stasis to weather extreme stress or danger.

In broader neurobiology, this type of nervous system response is understood as the body’s way of handling severe stress through hypoarousal—a state where overall activity decreases to conserve energy and protect vital functions. This response involves the entire autonomic nervous system.

Understanding these mechanisms—whether described as Dorsal Vagal Shutdown in Polyvagal Theory or as hypoarousal in broader neurobiology—helps us recognize the signs of this deep stress response. With this awareness, we can better support ourselves and others in navigating these challenging states.

Symptoms of a Dorsal Vagal Shutdown and Hypoarousal States

Dorsal Vagal Shutdown or hypoarousal states are natural defense mechanisms that the body and mind employ to protect themselves from overwhelming stress or trauma. These states can manifest in various ways, and recognizing the symptoms can help us offer the right support and compassion to those experiencing them:

Fatigue: An overwhelming exhaustion that isn’t linked to physical exertion, often leaving individuals feeling drained despite rest.

Dissociation: A sense of detachment from reality, making it difficult to stay present and engaged in the moment.

Numbness and Emotional Flatness: A significant reduction in the ability to feel or express emotions, leading to a sense of disconnection from oneself and others.

Cognitive Difficulties: Trouble with focus, clear thinking, and making decisions, often described as "brain fog."

Physical Immobilization: A feeling of being “frozen” or unable to move, even when there’s no physical reason for it.

Depression: Persistent feelings of sadness, hopelessness, or despair, which can be linked to the low-energy state of hypoarousal.

Blackouts: Brief periods of unconsciousness or memory loss, particularly in severe cases of stress or trauma response.

Chronic Dorsal Vagal Shutdown

Beyond immediate support, it’s crucial to recognize that for some individuals, Dorsal Vagal Shutdown can become a chronic condition. Chronic Dorsal Vagal Shutdown is understood within Polyvagal Theory as a prolonged state of dorsal vagal activation, where the body remains in a "freeze" response due to ongoing stress or trauma. This state presents a diffuse and persistent challenge, deeply affecting daily life and well-being.

From a broader neurobiological perspective, Chronic Dorsal Vagal Shutdown aligns with the concept of hypoarousal—a state where overall nervous system activity decreases to conserve energy in response to severe, prolonged stress. This hypoarousal state manifests through symptoms such as persistent fatigue, dissociation, emotional numbness, cognitive difficulties, physical immobilization, depression, and, in severe cases, blackouts. While these symptoms represent the body’s attempt to cope with extreme stress, they can significantly disrupt daily functioning.

Understanding the differences between acute and prolonged responses highlights the need for well-rounded treatment approaches. For Autistic individuals, experiencing chronic hypoarousal can lead to significant challenges, such as Autistic inertia and Autistic catatonia, which impact one’s ability to engage and respond effectively.

It’s important to recognize that, whether viewed through the lens of Polyvagal Theory or broader neurobiology, chronic hypoarousal signals deeper psychological issues, such as chronic stress or trauma, rather than being a disorder in itself. Treatment typically focuses on addressing these underlying issues through therapy, medication, and lifestyle adjustments aimed at stress management and self-care.

Additionally, it’s essential to rule out medical conditions that could mimic or exacerbate symptoms of hypoarousal-dominant nervous system states. Conditions like thyroid disorders, neurological issues, or vitamin deficiencies can present similar symptoms and should be considered during a comprehensive evaluation.

Seeking professional help is vital not only for therapeutic support but also for a thorough medical assessment to ensure a holistic approach to recovery. A mental health professional, working in collaboration with medical practitioners, can help identify the root causes—whether psychological, physical, or a combination—and develop an effective treatment plan tailored to the individual’s needs.

Difference Between Chronic and Acute Dorsal Vagal Shut Down

Dorsal Vagal Shutdown, often referred to as the body’s "freeze response" to overwhelming stress or trauma, is a natural and understandable reaction. This nervous system response can manifest in varying intensities and durations, leading to either acute or chronic states.

Acute Dorsal Vagal Shutdown is a temporary reaction to a specific stressor or traumatic event. This short-term response may last only a few hours or days and typically resolves as the individual processes the event and regains emotional and physiological balance. It’s similar to the body hitting a "pause" button, allowing for a brief period of recovery before returning to normal functioning. (In Polyvagal Theory, this is seen as a temporary activation of the dorsal vagal complex.)

Chronic Dorsal Vagal Shutdown, on the other hand, represents a prolonged state of hypoarousal that persists well beyond the immediate aftermath of a stressor or trauma. This extended shutdown can last for weeks, months, or even longer, significantly impacting both physical and mental health. Rather than being a standalone condition, chronic shutdown is a symptom of ongoing issues such as sustained stress, unresolved trauma, or other mental health challenges, indicating a deeper need for intervention. (Broader neurobiological perspectives describe this as a prolonged state of hypoarousal, involving reduced overall nervous system activity.)

The primary distinction between acute and chronic nervous system shutdown lies in their duration and the severity of their impact. While acute shutdown may serve as a temporary protective mechanism, chronic shutdown signals a profound disruption in the body’s and mind’s ability to manage and recover from stress.

Sensory Shutdowns and Dorsal Vagal Shutdown

Sensory overload can often lead to a sensory shutdown, where the nervous system reduces sensory processing as a protective response to overwhelming input. This state can sometimes precede or even trigger a Dorsal Vagal Shutdown or a hypoarousal nervous system state. When sensory overload becomes too intense, the nervous system may initiate a shutdown to protect the individual, significantly reducing both sensory perception and overall bodily function.

Recognizing the signs of impending sensory overload and employing strategies like using sensory supports or setting boundaries around sensory input can help prevent the transition into a more extensive shutdown state. By managing sensory input early, it's possible to mitigate the risk of entering a hypoarousal state. You can read more about sensory regulation over here.

How to Sooth a Dorsal Vagal Shutdown

Creating a safe, nurturing environment is crucial for anyone experiencing a Dorsal Vagal Shutdown (or hypoarousal in broader neurobiology). This involves ensuring both physical and emotional safety, helping the person regain a sense of stability and presence. When someone is in a deep state of shutdown, the goal is to slowly and gently help them reconnect with their body. Below are strategies to aid in gently increasing arousal or upregulating the nervous system.

Engage in Grounding Techniques: Grounding techniques that focus on reconnecting with the present moment can be particularly effective. These might involve tactile activities like holding a cold ice pack, touching various textures, or engaging in light, mindful exercises that gently activate the body without overwhelming it. Grounding helps bring awareness back to the physical body, which is essential for moving out of a shutdown state.

Create a Comforting Space: While a quiet, comfortable environment is important, it's also crucial to encourage gentle sensory engagement rather than complete isolation or sensory deprivation, which might deepen dissociation. The space should be calming yet offer opportunities for the person to engage their senses in a soothing way.

Upregulate with Sensory Input: Sensory inputs can delicately stimulate and awaken the senses, helping the body transition to a state of gentle alertness. Consider using soft, rhythmic music, visually calming elements like gentle videos or soft lamps, and the subtle invigoration from lightly scented oils. The grounding effect of a weighted blanket or the familiar scent of essential oils can also be comforting. These sensory tools encourage reconnection with the environment and assist in gradually shifting the nervous system toward a more balanced state, helping restore a sense of agency and physical control.

Engage in Gentle Movement: Gentle, mindful movement—such as walking, swaying, stretching, or yoga—can help individuals reconnect with their bodies and alleviate feelings of immobilization associated with a shutdown. Movement not only supports physical reconnection but also helps to restore a sense of agency and control, which is crucial for overcoming the freeze response.

Therapeutic Touch: For some individuals, therapeutic touch or self-massage with warm oils can be grounding and soothing. This tactile engagement reaffirms the body’s presence and capacity for sensation, aiding in the gradual process of reconnection. For those with a low tolerance for touch, weighted items can offer similar benefits by providing a sense of security and grounding.

Depth Work: While these practices can help gently awaken the nervous system, healing often requires more than just mechanical interventions. Acute experiences of hypoarousal are often rooted in deep-seated wounds, such as attachment wounds, trauma, and other emotional scars. This deeper therapeutic process—what I call avoiding Nervous System Bypassing—goes beyond surface-level interventions like breathwork.

Recovery from Dorsal Vagal Shutdown or hypoarousal states should be approached with patience and compassion. The journey back from such a profound state of disconnection is delicate and may require time and gentle exploration of what strategies feel most supportive.

Avoiding Nervous System Bypassing: The Importance of Depth Work

While the strategies listed above are effective for managing the immediate symptoms of Dorsal Vagal Shutdown or hypoarousal, it's essential to recognize that these techniques alone may not address the deeper, underlying causes of nervous system dysregulation. This is where the concept of nervous system bypassing comes into play—a term I use to describe the tendency to rely on surface-level and mechanical interventions without engaging in the necessary deeper work to heal underlying trauma, attachment wounds, or chronic stress.

Nervous system bypassing can occur when we focus solely on quick-fix solutions, such as breathwork or sensory tools, without addressing the root causes of our dysregulation. While these immediate strategies are invaluable for coping in the moment, they do not replace the need for comprehensive therapeutic work that tackles the core issues driving these nervous system states. This approach is often popularized by pop psychology and pop nervous system coaching, which may overlook the importance of depth work. Any program designed to support your nervous system needs to incorporate this deeper level of healing.

Depth work—including therapy that focuses on trauma, understanding attachment styles, and exploring triggers—provides a more lasting and profound healing process. By integrating both immediate regulation strategies and depth work, individuals can achieve true healing and resilience, rather than just managing symptoms.

It's important to approach nervous system regulation holistically, ensuring that we don't bypass the deeper work necessary for long-term well-being. By addressing both the symptoms and the underlying causes, we can create a more balanced and effective path to recovery.

Resources

Vagal Nerve Stimulators: Using a vagal nerve stimulator helps to strengthen your vagal tone which improves the flexibility of your nervous system! My personal favorite is the sensate. Use code NeuroInsights to get 10% off.

Biofeedback: 59 Breaths is a biofeedback program designed to improve heart rate variability and nervous system flexibility. (Note only works with Apple Watch). Use this link to get $20 off the annual subscription.

Workbook: For more of a deep dive on the nervous system you can check out the Neurodivergent Nervous System digital workbook here.

Free Blog Posts: I have several free blog posts up on nervous system regulation practices and strategies.

Summary: Dorsal Vagal Shutdown

Dorsal Vagal Shutdown, also referred to as hypoarousal in broader neurobiology, is a "freeze response" that occurs when the nervous system is overwhelmed by stress or trauma. This natural response allows the body to conserve energy and protect itself when neither fight nor flight is possible. Symptoms of Dorsal Vagal Shutdown can include persistent fatigue, dissociation, emotional numbness, cognitive fog, physical immobilization, depression, and in severe cases, blackouts.

While the concept of Dorsal Vagal Shutdown within Polyvagal Theory is critiqued and debated, the broader concept of hypoarousal is widely recognized and well-established in neurobiology. Creating a safe and supportive environment is crucial for those experiencing Dorsal Vagal Shutdown or hypoarousal. Gentle strategies, such as grounding techniques, sensory support, and mindful movement, can help in gradually reactivating the nervous system. However, it’s also essential to address deeper underlying issues, such as unresolved trauma or attachment wounds, through professional support and depth work.

By understanding and recognizing the signs of nervous system shutdowns, we can offer effective support and foster resilience.

References

Beauchaine, T. P., Gatzke-Kopp, L., Neuhaus, E., Chipman, J., Reid, M. J., & Webster-Stratton, C. (2013). Sympathetic- and parasympathetic-linked cardiac function and prediction of externalizing behavior, emotion regulation, and prosocial behavior among preschoolers treated for ADHD. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 81(3), 481–493. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032302

Bellato, A., Arora, I., Hollis, C., & Groom, M. J. (2020). Is autonomic nervous system function atypical in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)? A systematic review of the evidence. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 108, 182-206.

Beutler, S., Mertens, Y. L., Ladner, L., Schellong, J., Croy, I., & Daniels, J. K. (2022). Trauma-related dissociation and the autonomic nervous system: a systematic literature review of psychophysiological correlates of dissociative experiencing in PTSD patients. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 13(2).

Gourine, A. V., & Ackland, G. L. (2019). Cardiac vagus and exercise. Physiology, 34(1), 71-80.

Fenning, R. M., Erath, S. A., Baker, J. K., Messinger, D. S., Moffitt, J., Baucom, B. R., & Kaeppler, A. K. (2019). Sympathetic-Parasympathetic Interaction and Externalizing Problems in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Autism research : official journal of the International Society for Autism Research, 12(12), 1805–1816.

Porges, S. W. (2001). The polyvagal theory: phylogenetic substrates of a social nervous system. International journal of psychophysiology, 42(2), 123-146.

Schmidt, N. B., Richey, J. A., Zvolensky, M. J., & Maner, J. K. (2008). Exploring human freeze responses to a threat stressor. Journal of behavior therapy and experimental psychiatry, 39(3), 292–304.

Spratt, E. G., Nicholas, J. S., Brady, K. T., Carpenter, L. A., Hatcher, C. R., Meekins, K. A., ... & Charles, J. M. (2012). Enhanced cortisol response to stress in children in autism. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 42, 75-81.