The Autistic and ADHD Nervous System

The Autistic and ADHD nervous system is a vulnerable and sensitive thing. Sometimes, as neurodivergent people, we struggle to adapt to change, stress, and conflict. More often than neurotypicals, we experience panic attacks, anxiety and depression disorders, difficulty regulating our emotions, and more. The answers as to why that is and what we can do to change that rigidity are in understanding the nervous system.

When I’m working with my neurodivergent clients, part of what I do is help them understand what’s going on in their nervous system. As an Autistic person and ADHDer myself, I know first-hand how important this understanding is. When we learn about our nervous systems, we can begin taking our power back. We learn the reasons why our nervous systems behave the way they do so that we can learn how to influence them for our health and overall benefit.

In this article, you will learn about your nervous system and learn about ways you can begin to create more balance. If you are looking for more specific help learning about nervous system exercises and want help implementing them, I recommend checking out my Nervous System Workbook, here, you’ll learn about your own nervous system, track symptoms, and get workbook pages to help you begin introducing exercises into your routines.

How to Use the Article

There’s a lot of information here packed into one article. So please take your time and come back if you need to. At the end of this article, there are some suggestions and exercises to try out. As with those, it’s best to try them one or two at a time. Too many changes to a routine at once can be overwhelming to the body and do more harm than good. So I recommend going slow while you’re experimenting with the exercises and adding them into your routine.

Before diving into the neurodivergent nervous system, let’s do a refresher on what we even mean when we’re talking about “the nervous system.”

Autistic & ADHD Nervous System Anatomy & Physiology

In the human nervous system, there are two major parts. First is the central nervous system (CNS), which is made up of the brain and the spinal cord. Simply, the central nervous system is responsible for receiving sensory signals, processing information, and sending motor signals to the body. This is like the control center for the nervous system. No sensation exists until the signal hits the brain.

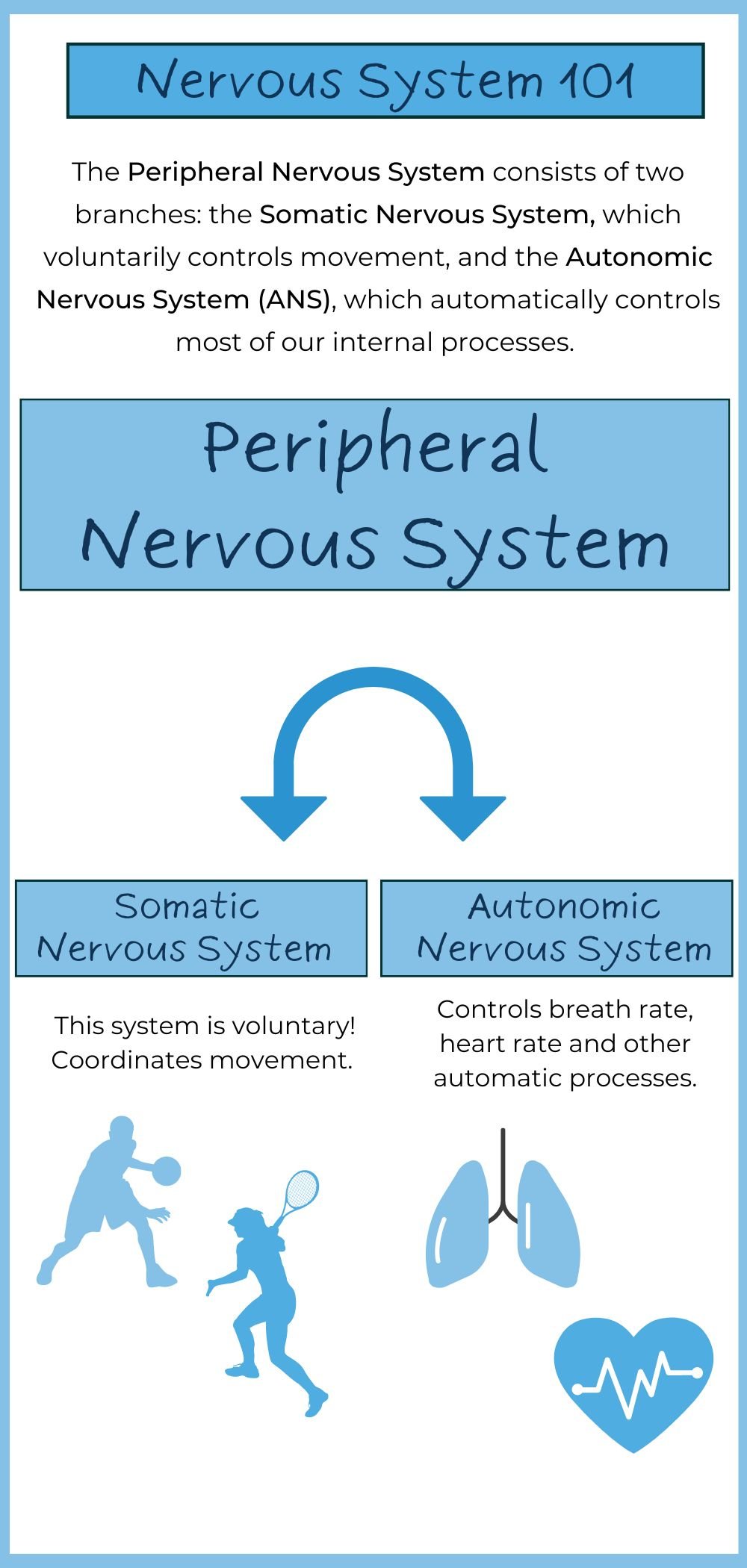

The second is the peripheral nervous system (PNS), which comprises all nerves, neurons, and ganglia outside of the brain and spinal cord in the rest of the body. This system is responsible for sending commands from the CNS to the body via motor neurons and receiving information about the internal and external environment via sensory neurons. The PNS plays a vital role in the mind-body connection.

The Peripheral Nervous System

Let’s zero in on the peripheral nervous system for a moment. The PNS can also be divided into two major parts. The first is the somatic nervous system. The somatic nervous system is voluntary and is responsible for all voluntary movement. So when you open and close your hand or kick a soccer ball, those movements are controlled by the somatic nervous system.

The second part of the PNS is the autonomic nervous system. This system is responsible for all movements of the body that are not in our conscious control. For example, our digestion, heart rate, blood pressure, metabolism, breathing rate (most of the time), and more are all under the control of this system. These things happen on an autonomic level, much like a sneeze.

When we’re talking about trauma, anxiety, nervous system regulation, etc., the autonomic nervous system is the most important player. Therefore, for the rest of the article, we are going to focus on this nervous system: learning about it and learning how to influence it.

The Autonomic Nervous System

Like the other broader categories of the human nervous system, the autonomic nervous system can also be divided into two parts. First is the sympathetic nervous system, and second is the parasympathetic nervous system. In a regulated body (aka one that is balanced), both of these systems work together similarly to the gas and the brake pedal in a car. The sympathetic nervous system is like the gas pedal, activating and accelerating the body’s systems. For example, when your heart rate increases, that is the result of sympathetic nervous system activation. The parasympathetic nervous system is like the brake, working to slow the body’s systems down. For example, when your heart rate slows, this is the parasympathetic nervous system at work.

The hypothalamus, a part of the brain, is what is in control of these two systems. This part of the brain is what is responsible for the body’s state of homeostasis and therefore acts like the driver of the car. In a regulated body, the hypothalamus can smoothly use both systems to keep us in a state of nervous system balance.

Let’s get into what this looks like in more detail.

The Sympathetic Nervous System

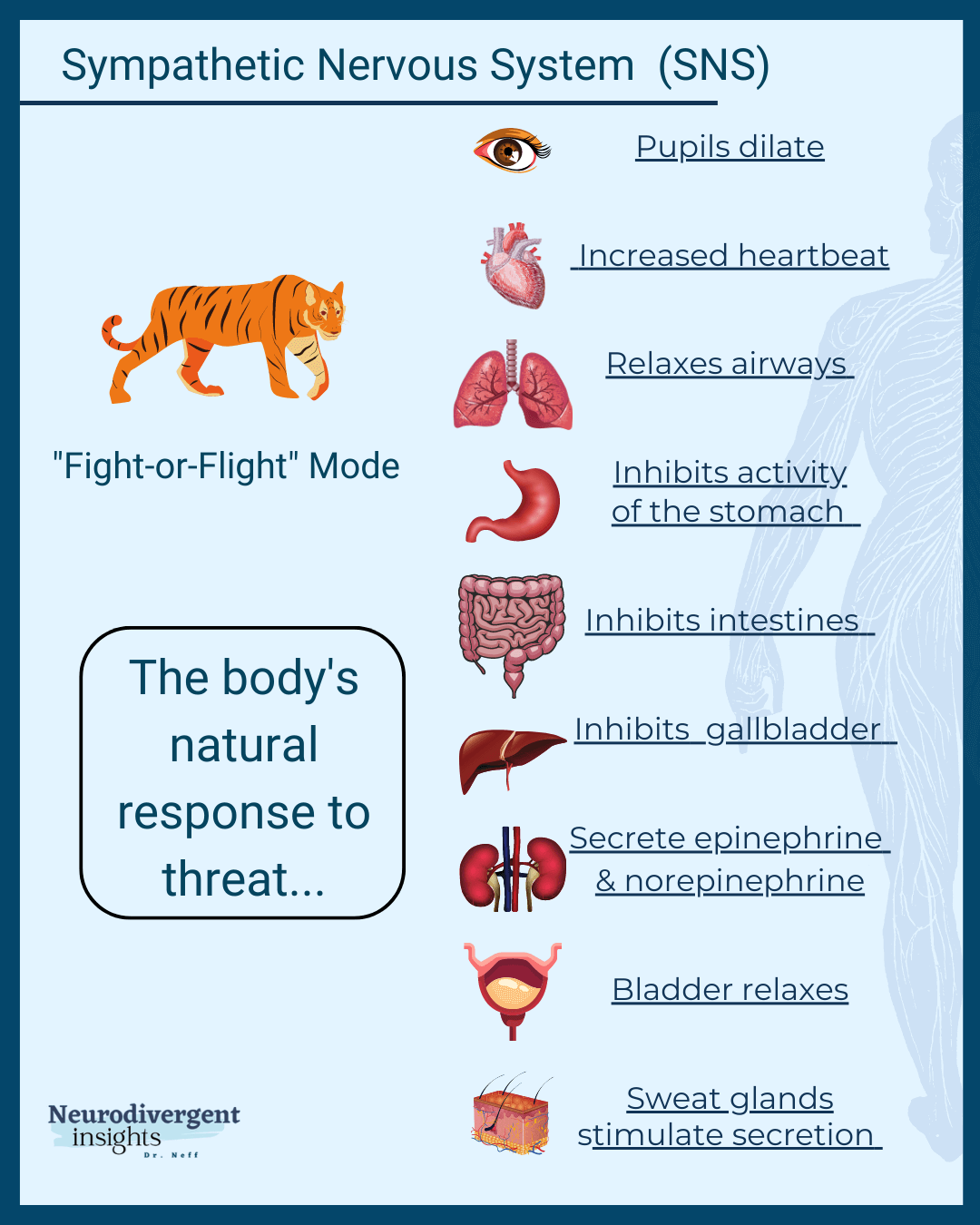

The sympathetic nervous system is responsible for activating the body. When we are stressed, we can really see this system in action. The sympathetic nervous system kicks on our “fight or flight” response when we are stressed. Several things happen when our fight-or-flight is activated: our heart rate, breathing rate, and blood pressure increase. Pupils dilate, our muscles tense, and more. All of this is to protect the body from threats by mobilizing us for action. These physical changes are accompanied by hormonal ones. During a stress response, we get a rush of adrenaline and cortisol which boost our energy and further help the body prepare to deal with the stressors.

Here is a list of changes that happen to the body when our sympathetic nervous system, or “fight or flight” response, is activated:

Rapid and varied heart rate

Fast, shallow breathing

Increased blood pressure

Dilated pupils

High levels of adrenaline and cortisol

Muscle tension

Increased energy

Increased vigilance

Narrow focus

Slow digestion

Poor immune system function

Decreased sexual arousal

All of these changes happen to help us better fight the stressors or run away from them, take in critical information about our environment, and slow down bodily processes that aren’t necessary to keep us safe at the moment (such as digestion).

But remember, all of this is unconscious. That means that whatever the body sees as a threat, its threat response will activate—regardless of how reasonable you think it is! So whether you are stalked by an animal in the woods or your boss tells you they need to talk to you privately, the stress response will be the same. For neurodivergent people, because our bodies are more sensitive to stimulation than the average neurotypical person, a loud sound or an unexpected touch can trigger this stress response, too.

The Parasympathetic Nervous System

Working in the opposite direction, the parasympathetic nervous system is what allows our bodies to slow down. This system is what is responsible for our state of “rest and digest.” You may be able to see this system in action at the end of the day, while you’re stretching, or while you’re meditating. When you take the time to rest, your heart and breathing rate decrease, you take fuller breaths, your muscles relax, and so on. Like how sympathetic activation is critical to keep us safe and alive, parasympathetic activation is critical for us to properly recover. Parasympathetic activation allows our digestive systems to properly digest our food, our bodies to heal and fight off infections, and our minds to go to sleep.

When we’re in this state of “rest and digest"” this is what’s going on inside our bodies:

Slow and stable heart rate

Deep breathing

Decreased blood pressure

Relaxed pupils

Low levels of adrenaline and cortisol

Relaxed muscles

Decreased energy or sleepiness

Decreased vigilance

Broad awareness

Increased digestion

Increased immune system function and bodily repair

Increased sexual arousal

Like the sympathetic nervous system, this system is completely unconscious. That means that our bodies turn on our “rest and digest” responses only after assessing our environment and deeming it safe—regardless of how relaxed you think you should be. For neurotypicals, resting is relatively easy because their bodies aren’t picking up as much information as ours usually do. But it can be difficult for those with neurodivergence or trauma to convince our bodies they’re safe.

Before jumping into what it looks like for these two systems to be out of balance and what that means for neurodivergent people, let’s first go into more detail about what’s at play when assessing how regulated our nervous systems are. When getting to know our autonomic nervous system, there are two things we focus on: the vagus nerve and vagal tone.

The Vagus Nerve

The 10th cranial nerve, also known as the vagus nerve, plays a vital role in the parasympathetic nervous system, which is crucial for maintaining bodily functions during rest. Its name, derived from the Latin word "vagus," meaning "wanderer," reflects its extensive reach throughout the body. The vagus nerve connects the brain to many major organs, including the heart, lungs, and digestive system. It regulates essential functions such as heart rate, digestion, breathing, and even reflex actions like coughing and swallowing.

The vagus nerve's broad influence is particularly notable in the gut-brain axis, where it helps regulate digestion and communicates signals between the brain and the gastrointestinal system. This nerve is also involved in modulating the body's response to stress, helping to calm the body after periods of activation by the sympathetic nervous system.

The vagus nerve also plays a crucial role in the flexibility of the nervous system, facilitating the harmonious interaction between the sympathetic and parasympathetic branches to maintain balance and respond to changing conditions.

Vagal Tone

“Vagal tone” refers to the activity of the vagus nerve. High vagal tone indicates a more flexible nervous system, where the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems work together harmoniously. In contrast, low vagal tone means the vagus nerve struggles to adapt between these systems, leading to increased strain and stress on the nervous system. Research has shown that Autistic and ADHD individuals often have low vagal tone, contributing to what I call a “rigid nervous system.”

When discussing nervous system healing and improving resilience to stress, enhancing vagal tone is crucial. A higher vagal tone expands one's window of tolerance, allowing for better stress management and adaptability.

Autistic & ADHD Nervous System and The Window of Tolerance

When our nervous systems are in balance, we are in what’s called the window of tolerance. Here, our minds and bodies can easily and efficiently respond to stress, we are present and calm, and we quickly recover from stress. However, the window of tolerance has its limits. When we experience extreme stress that we’re unable to recover from or when we are continuously exposed to stressors without the support or time we need to work through them smoothly, we exit the window of tolerance and enter either hyperarousal or hypoarousal.

Hyperarousal

When we exit our window of tolerance, we may enter a state of hyperarousal. In this state, the body is mobilized for action, preparing to face perceived danger, with the sympathetic nervous system (responsible for the "fight or flight" response) becoming highly active. This heightened state leads to increased energy, vigilance, and physical readiness. However, when sustained, hyperarousal can result in feelings of anger, anxiety, hypervigilance, and even paranoia.

Historically, hyperarousal was an adaptive response to immediate threats, helping our ancestors survive dangerous situations. After such events, it was important to "shake off" the excess energy to return to a state of balance. However, modern life presents many subtle, chronic stressors—like public speaking, financial pressures, or interpersonal conflicts—that can keep us stuck in a state of hyperarousal. Because our bodies react similarly to these stressors as they would to immediate physical danger, many people find themselves unable to exit this stress cycle, leading to prolonged periods of hyperarousal.

Hypoarousal

In response to acute stress, the body may enter a state of hypoarousal, characterized by immobilization and shutdown. Unlike hyperarousal, which is associated with the sympathetic nervous system, hypoarousal is linked to a significant decrease in nervous system activity. The body and mind slow down, resulting in symptoms such as fatigue, dissociation, numbness, foggy thinking, and even physical immobilization.

This response is thought to be an evolutionary adaptation designed to protect the body from overwhelming stress or trauma. By reducing sensory input and mental activity, the body minimizes the experience of pain and stress, similar to how some animals "play dead" when threatened. This state can be protective in the short term but can lead to significant challenges if it becomes chronic.

In modern life, prolonged exposure to stressors without adequate recovery can trap the body in this state of hypoarousal, leading to symptoms like chronic fatigue, headaches, and low-grade dissociation. This occurs because the body struggles to find safety and remains in a state of defensive shutdown.

Understanding the Freeze State

The freeze response is a natural reaction to overwhelming stress or perceived threats, where the body becomes immobilized. Unlike hyperarousal, where you're ready to fight or flee, or hypoarousal, where everything slows down, the freeze response involves both systems at once—your body is primed for action but also paralyzed.

This response was likely useful in ancient times when staying still could mean survival. For neurodivergent people, especially those sensitive to sensory input or with trauma histories, the freeze response might kick in during situations that feel overwhelming, even if they're not life-threatening.

Faux Regulation

Before leaving the conversation of hypoarousal and the freeze state it’s important to note faux regulation. Faux regulation is when a person looks regulated on the outside to others, but is internally stressed and dysregulated. When we are in a state of faux regulation, our nervous systems are shut down and in a hypoaroused state. So to others, we appear calm and collected, but on the inside, we are frozen and numb. Autistic people are especially prone to this. This is why, when we have a sensory shutdown we can appear calm to everyone else. This is particularly true among high-masking Autistic people who have learned to survive by shutting our bodies down.

Understanding Your Window of Tolerance

When we are in our window of tolerance, we feel mindful, curious, open, engaged, and present. We effectively manage our emotions and stress. The larger our window of tolerance, the more we can handle while staying in this present state. A large window of tolerance equals a healthy, regulated nervous system.

However, if our window of tolerance is small, we quickly get triggered in a dysregulated state—we quickly become hyperaroused (angry, anxious, irritable, etc.) or hypoaroused (frozen, dissociated, numb, etc.). There are plenty of reasons why someone’s window of tolerance may be small, including PTSD, neurodivergence, anxiety disorders, and more. Neurodivergent nervous systems tend to be more rigid than neurotypical ones, therefore, our window of tolerance tends to be smaller.

Expanding the Window of Tolerance in Autistic & ADHD Nervous Systems

If you want to begin to expand your window of tolerance, then it’s important to begin with understanding it. By regularly checking in with your body and using the provided infographics, you can notice where your nervous system is at any given time. And by consistently checking in in this way over time, we begin to see nervous system patterns and can track and observe when we are in our window of tolerance. Once we have that information, we can introduce exercises to expand this window.

Heart Rate Variability

One key factor in measuring vagal tone and the window of tolerance is tracking heart-rate variability (HRV). HRV measures how much variation there is in your heart rate over time and in changing situations. Someone with a high vagal tone—or a large window of tolerance—has more variation in heart rate and increased HRV. Likewise, someone with a low vagal tone has low HRV.

If you’d like to track your HRV, using an Apple Watch or a FitBit is the best way. By writing down your HRV each week, both before and after beginning to introduce vagal tone exercises, you get to witness your nervous system building more capacity.

Increasing Vagal Tone

This section is full of lifestyle changes and habits you can make to increase your vagal tone. By increasing your vagal tone, you increase your tolerance for stress and increase adaptability, relaxation, curiosity, and a sense of safety. Living in a nervous system that is easily triggered, vigilant, or shut down creates more fear, discomfort, and lack of fulfillment. Everyone deserves to live in a regulated nervous system! So here are some ways you can begin working toward that internal stability.

Remember: please take it slow. These practices cannot be made all at once. By making too many changes at one time, you can overwhelm the nervous system and cause it to resist the exercises. The goal here is to create safety, which means moving slowly and mindfully. We can’t heal with the same hustle that caused the trauma! I recommend starting with one exercise (whatever calls to you first) and working with that for a few weeks to a month before moving on. When we’re dealing with rigid or traumatized nervous systems, they require that we show them a lot of proof that we’re safe before they begin to relax.

Besides working through these exercises, I also recommend seeing a somatic practitioner. They’ll be able to help you better integrate these practices into what your body specifically needs.

Breathwork

You’ve probably heard it a million times, but breath work is one of the best practices for regulation. Slow, deep breathing activates the vagus nerve and, therefore, the parasympathetic nervous system. It helps to ease anxiety, refocus the mind, and ground the body. Likewise, fast-shallow breathing activates the sympathetic nervous system and creates activation when the body is stuck in an immobilized state.

Cold Exposure

Studies have shown that cold exposure increases vagal activity and HRV as well as decreasing sympathetic responses. Cold exposure can look like adding 30 seconds of cold water to the end of a shower, dipping your face in a bowl of ice water, or putting ice on the back of your neck for 30 seconds to a minute. Cold exposure to the neck has been shown to be particularly effective.

Exercise and Movement

Exercise has been shown to increase HRV by stimulating and toning the vagus nerve. Vigorous movement (like taking long walks or going for runs), weightlifting, and somatic movement are all great options for increasing vagal tone. However, because neurodivergent people often have hyper-mobility and joint issues, be sure to be gentle with your body whatever kind of movement you decide to do.

Weight lifting has the added benefit of putting deep pressure on the joints, which many neurodivergent people find relaxing. Somatic movement is especially useful for healing trauma and relaxing the body in a mindful way. Dr. Sam Zoranovich is a queer and neurodivergent-affirming chiropractor and has many great resources for neurodivergent-friendly somatic movement exercises.

Mindfulness and Meditation

Contemplative practices have been shown to have many benefits to mental health. Not only is meditation linked to decreased brain inflammation, better memory, and increased ability to learn new information, but it is also linked to increased HRV and vagal tone. Specifically, mindfulness has the ability to activate the vagus nerve, especially when there is breathwork involved. As an added bonus, mindfulness practices can help to increase interoception (the ability to monitor internal states like hunger, thirst, sleepiness, etc.), which many Autistic people and ADHDers struggle with.

Probiotics and Omega-3s

In what is called the gut-brain axis, researchers have shown there is a huge connection between gut health and mental health. Like how the vagus nerve is connected to organs like the heart, it is also deeply interconnected with the gut. It is, after all, responsible for digestion. Therefore, the gut and microbiome communicate with the brain via the vagus nerve, meaning, when the gut is stressed, so is the vagus nerve. By taking care of our gut with probiotics and omega-3s, we can, in turn, take care of our nervous system.

Laughter

Laughter really is the best medicine! Studies have shown that laughter stimulates the vagus nerve by inducing diaphragmatic breathing. Only about ten minutes of laughter per day is shown to have many health benefits. Try adding more comedy in your life or some intentional laughter meditation!

Humming, Chanting, and Singing

Chanting can be found in many cultures around the world, and for a reason! Humming, chanting and singing are very powerful ways of activating the vagus nerve. One study even showed that chanting “om” can deactivate the limbic center of the brain, which is responsible for threat and emotion. The Vagus nerve is interconnected with our vocal cords and the muscles at the back of the throat. Therefore, using your vocal cords in mindful ways directly activates this nerve.

Massage

Massage is another great way to increase vagal tone. Human contact is so important, and many of us are walking around touch starved. Mindful human-to-human contact both stimulates the vagus nerve and increases oxytocin, the bonding hormone. Although you can get this kind of massage from someone else, there are also ways to give yourself simple massages. This video by Sukie Baker is an example.

Havening

Havening is a form of self-soothing by creating safety through comforting, therapeutic touch. Havening involves a distinctive self-soothing touch that creates a haven for yourself. The theory rests on the idea that soothing touch boosts the production of serotonin. Serotonin has a soothing effect. Specific motions such as cupping your hands on your cheeks, holding a hand across your chest, or crossing your arms (as if giving yourself a hug) while striking your shoulders and upper arms. This creates a sense of safety and wellbeing through your touch (note many Autistic people have a preference for deep pressure, be sure and apply a pressure that feels good).

Relaxation Exercises

Last, but certainly not least, is relaxation exercises. Relaxation exercises are arguably the most important tool in our regulation toolbox. These exercises directly target the ventral vagal system to calm the body out of dysregulation. We can use them before bed, to ground ourselves in the morning, to recover for stressful events, or to more mindfully engage in conflict. These exercises can include a variety of breathing techniques, progressive muscle relaxation (PMR), and meditations.

Conclusion: the Autistic & ADHD Nervous System

Understanding our nervous system is an important part of learning how to regulate ourselves. In this article we’ve learned about the autonomic nervous system, which is a part of the peripheral branch of the nervous system. In a regulated body, the sympathetic and the parasympathetic nervous systems work together to skillfully adapt to stress and changes in the environment. However, when our nervous systems are rigid (have a small window of tolerance) because of neurodivergence or trauma, we can easily fall into dysregulation, characterized by hyperarousal and hypoarousal.

However, there is always hope for us. By learning about our own vagal tone and window of tolerance, then introducing exercises to increase vagal tone, we can grow our window of tolerance over time.

If you’ve found this information helpful and want more guidance, I have a workbook all about the neurodivergent nervous system with worksheets to help you better get to know yours. In the workbook, you’ll find the information in this article alongside guides and step-by-step worksheets so you can learn about your own window of tolerance and to begin to implement some of these regulation exercises in your daily routines. Get it here.

Citations

Beauchaine, T. P., Gatzke-Kopp, L., Neuhaus, E., Chipman, J., Reid, M. J., & Webster-Stratton, C. (2013). Sympathetic- and parasympathetic-linked cardiac function and prediction of externalizing behavior, emotion regulation, and prosocial behavior among preschoolers treated for ADHD. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 81(3), 481–493. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032302

Bellato, A., Arora, I., Hollis, C., & Groom, M. J. (2020). Is autonomic nervous system function atypical in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)? A systematic review of the evidence. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 108, 182-206.

Bergland, C. (2016, September 18). How self-initiated laughter can make you feel better. Psychology Today.

Christensen J. H. (2011). Omega-3 polyunsaturated Fatty acids and heart rate variability. Frontiers in physiology, 2, 84. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2011.00084

Jungmann, M., Vencatachellum, S., Van Ryckeghem, D., & Vögele, C. (2018). Effects of Cold Stimulation on Cardiac-Vagal Activation in Healthy Participants: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR formative research, 2(2), e10257.

Fenning, R. M., Erath, S. A., Baker, J. K., Messinger, D. S., Moffitt, J., Baucom, B. R., & Kaeppler, A. K. (2019). Sympathetic-Parasympathetic Interaction and Externalizing Problems in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Autism research : official journal of the International Society for Autism Research, 12(12), 1805–1816.

Gourine, A. V., & Ackland, G. L. (2018). Cardiac vagus and exercise. Physiology, 33(6), 486-487.

Gerritsen, R. J. S., & Band, G. P. H. (2018). Breath of Life: The Respiratory Vagal Stimulation Model of Contemplative Activity. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 12, 397. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2018.00397

Spratt, E. G., Nicholas, J. S., Brady, K. T., & et al. (2012). Enhanced cortisol response to stress in children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(1), 75-81.

Old Graphics

Understanding the Freeze State

The freeze state is a specific response to overwhelming stress or threat, distinct from both hyperarousal and hypoarousal. Unlike hyperarousal, where the body is mobilized for action, or hypoarousal, where the body shuts down to conserve energy, the freeze response is a state of immobility that involves both sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system activation. This mixed state is often characterized by a sudden halt in movement, where the body is simultaneously prepared for action (sympathetic activation) but also immobilized (parasympathetic activation).