How are Autism and Trauma Related?

Autism and Trauma

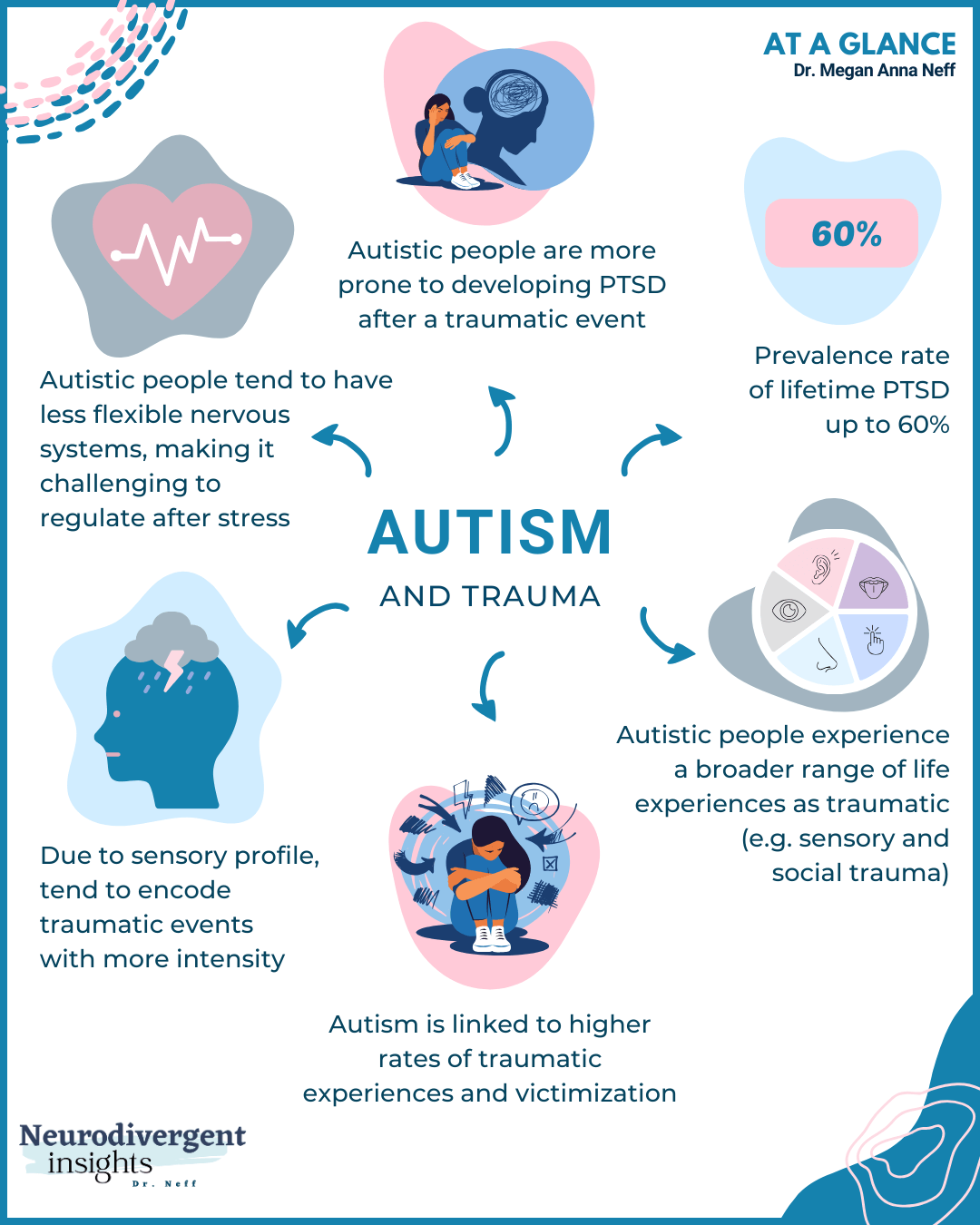

Autism and trauma often co-occur, yet this intersection remains under-researched and seldom highlighted in clinical training. Autistic people are at a significantly higher risk of developing PTSD after experiencing trauma due to several factors that intertwine their neurobiology with their social experiences. A recent study highlighted that even when criteria A of PTSD (Big T Trauma) is not met, Autistic people will often develop PTSD symptoms (Rumball et al., 2020). While there are several factors, here are a few of the reasons Autistic people may be more vulnerable to developing PTSD following a traumatic experience.

We have more vulnerable neurobiology (more reactive nervous systems)

Increased risk of victimization

Sensitive sensory profiles that encode memory with more intensity

The chronic stress and invalidation of navigating an allistic world.

Let’s break these down a bit more, but first, let’s review some of the studies that have looked at the prevalence rates of PTSD among Autistic people.

The Prevalence of PTSD Among Autistic Individuals

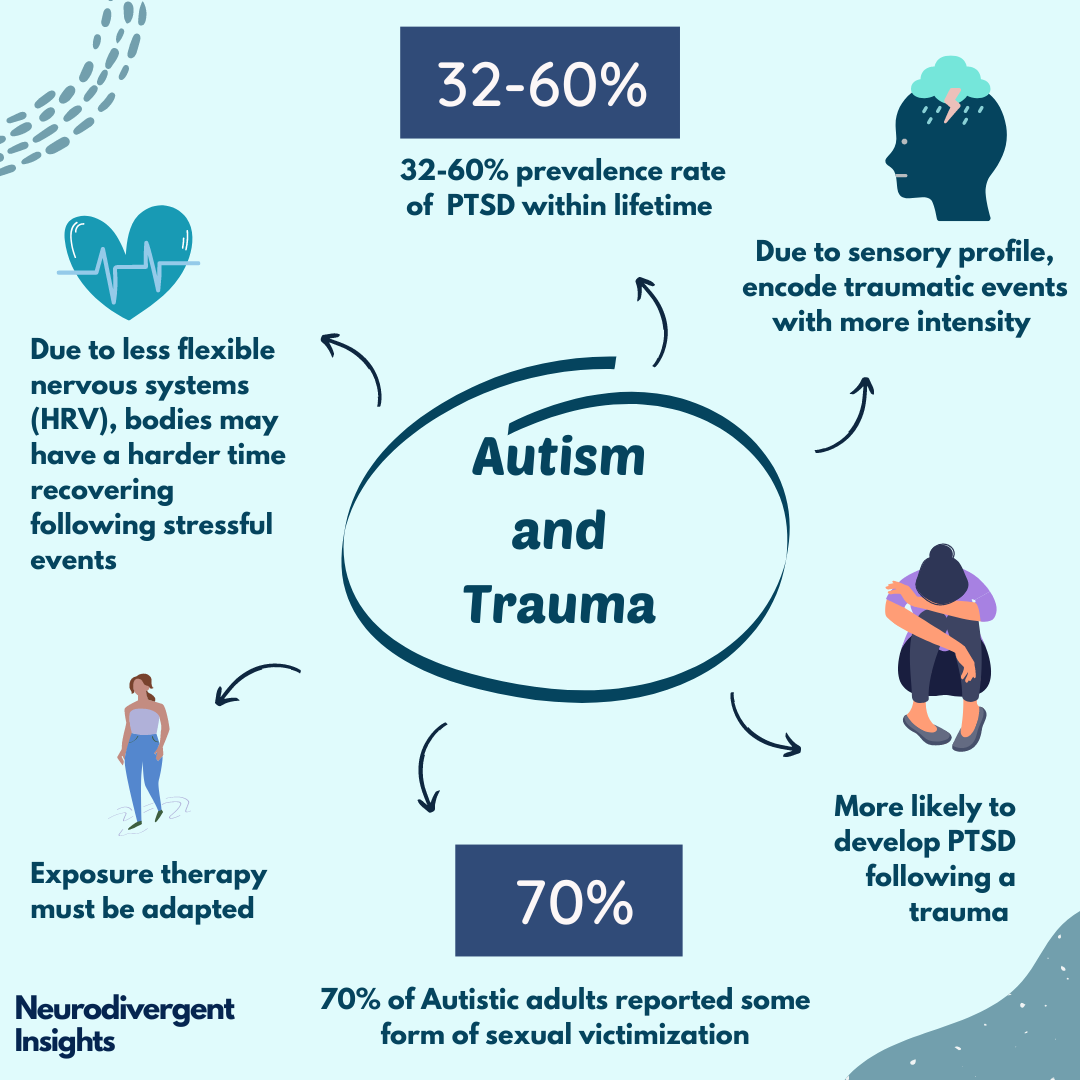

Several studies highlight the disproportionately high rates of PTSD within the Autistic community compared to the general population. A study by Rumball et al. (2020) found that approximately 60% of Autistic people reported probable PTSD in their lifetime, compared to just 4.5% of the general population. Similarly, Haruvi-Lamdan et al. (2020) found that 32% of their Autistic participants had probable PTSD, compared to only 4% of the non-autistic population.

Double-Sided Risk

As Autistic individuals, we face a double-sided risk. On one hand, we are more likely to experience traumatic events, including various forms of victimization. Additionally, we often perceive and experience things that others do not consider traumatic, such as sensory-based trauma and social trauma, as intensely distressing. Beyond traditional PTSD triggers, we often experience a broader range of life events as traumatic. On the other hand, our systems are more vulnerable to developing acute stress responses and PTSD in the aftermath of these traumas. This heightened sensitivity and increased exposure to trauma underscore our increased vulnerability to stress reactions as we move through the world.

More Vulnerable Neurobiology

Autistic individuals often have more reactive nervous systems, making us more susceptible to PTSD (Beauchaine et al., 2013). Research demonstrates that Autistic children exhibit heightened nervous system reactivity and less flexibility in managing stressors. For example, Fenning et al, 2019 found that Autistic children had more reactive nervous systems, aligning with similar research by Thapa and Alvares, 2019, which identified the Autistic nervous system as less flexible. This reduced flexibility hampers their ability to cope with acute stressors, contributing to the higher incidence of PTSD. This hyperactivation can lead to increased vulnerability following trauma.

Social Victimization and Marginalization

Autistic people, particularly women and genderqueer people, are at greater risk of social victimization. Haruvi-Lamdan et al. (2020) found that Autistic females reported more negative life events, particularly social events, than their neurotypical peers. This increased exposure to adverse social experiences further compounds their risk of developing PTSD.

Moreover, Brown-Lavoie et al. (2014) found that 70% of Autistic adults reported experiencing some form of sexual victimization after the age of 14, compared to 45% of the control group. This staggering statistic highlights the increased vulnerability that Autistic people experience as they navigate the world.

Sensitive Sensory Profiles

Autistic people often have sensitive sensory profiles, which means our experiences are encoded with greater intensity. This can result in a heightened sensory memory associated with trauma. The detailed-oriented processing typical of Autistic individuals means that sensory aspects of traumatic events are vividly remembered, which can exacerbate PTSD symptoms. Rumball et al. (2020) emphasized how sensory experiences could intensify trauma memories, necessitating an understanding of these sensory profiles in trauma treatment.

Chronic Stress and Invalidation of Navigating an Allistic World

Living in a world designed for neurotypical (allistic) individuals presents constant stress and invalidation for Autistic people. This chronic stress can exacerbate the risk of developing PTSD. Autistic people often face daily challenges in cross-neurotype communication and interactions, and sensory processing, which can lead to chronic stress, hyperarousal and anxiety. The ongoing need to mask or suppress Autistic traits to fit into societal norms further compounds this stress, making us more vulnerable to mood conditions and acute stress responses.

Additional Considerations

Autistic people who mask their traits are more likely to be diagnosed with PTSD while their neurotype goes unnoticed. This means they are less likely to receive autistic-adapted treatments for their PTSD.

Undiagnosed Autistic people are also less likely to receive education about their increased risk of both victimization and developing PTSD following stressful events. This is why I always say that an accurate and timely diagnosis of autism is trauma prevention.

Additionally, when a person’s Autistic identity intersects with other marginalized identities, the risks, stress, and strain of the above factors increase.

Autistic Adapted Trauma Treatment

Given these vulnerabilities, traditional PTSD treatments like exposure therapy may not always be suitable for Autistic individuals. Adapting these therapies to account for the distinct sensory and cognitive experiences of Autistic clients is critical for neurodivergent-affirming care and support.

Sensory Sensitivities and Environment

Autistic people often do not habituate to sensory stimuli in the same way neurotypical individuals do. Therefore, it is essential to create a sensory-soothing environment during therapy to minimize additional stress. Therapists should be mindful of sensory irritants that could exacerbate stress and interfere with progress.

Trauma Narratives and Sensory Encoding

Due to our detail-oriented processing, many Autistic people have heightened sensory memories associated with trauma (Rumball et al., 2020). Therapists need to consider this when working with trauma narratives and exposure-based therapies. Understanding how these sensory memories affect the individual can help tailor the treatment to be more effective and less distressing.

Meltdowns vs. Trauma Triggers

Differentiating between meltdowns and trauma triggers is essential. Meltdowns can occur due to sensory overload, such as loud noises or bright lights, and are not necessarily linked to past traumatic events. Trauma triggers, however, are reactions to stimuli that remind the individual of past trauma, causing emotional and physical distress.

Psychoeducation and Engagement

Psychoeducation is a cornerstone of effective trauma treatment, particularly for Autistic clients. Psychoeducation helps explain to the client what is happening to their bodies, providing clarity and understanding, which are especially critical for Autistic people to move forward. Providing clear expectations reduces uncertainty and fosters psychological safety. Using visual aids, drawings, and incorporating special interests can make psychoeducation more accessible for Autistic clients.

Working with Alexithymia

Alexithymia, the difficulty identifying and describing emotions, is more common among Autistic people. Complicating matters, alexithymia can also develop as part of PTSD. An Autistic person may have a baseline (innate) alexithymia, which can be exacerbated by PTSD symptoms. Learning how to work with alexithymia and help clients recognize different emotional and bodily states is key to autistic-adapted trauma treatment. This involves developing strategies to increase emotional awareness and expression, which can significantly increase the effectiveness of trauma therapy for Autistic individuals. It also means avoiding emotion and body-based questions that are out of context with the client’s alexithymia, as this can make the client feel incompetent or overwhelmed.

Incorporating Special Interests

Special interests can be powerful tools for self-soothing and distraction. While distraction is often viewed as emotional avoidance, it can be beneficial when managing sensory meltdowns. Therapists should not hesitate to incorporate special interests into treatment plans to help clients manage their sensory experiences.

Tailoring Exposure Treatment to Autistic Needs

When using exposure therapy with Autistic people, it should be adapted and led by the client. Trauma treatment should take into account the individual's sensory experience, incorporate special interests and visual education, grounding techniques, bodywork, and encourage natural forms of movement for regulation.

Some effective trauma treatments for Autistic people may include Somatic Therapies, EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing), and Internal Family Systems Theory. However, it's important to recognize that each Autistic person is unique, and what works for one may not work the same way for another. Tailoring the approach to the individual's specific need and pace is critical.

Conclusion

Understanding the distinct vulnerabilities and needs of Autistic people is key for effective trauma treatment. By tailoring traditional therapies to fit Autistic experiences, we can offer more attuned and affirming care.

Timely and accurate autism diagnosis is essential, as it guides proper treatment and buffers from further trauma. In a world that often misses the link between autism and trauma, recognizing and addressing these challenges is key to providing trauma-informed and neurodivergent-informed care.

Further Learning

Books for Trauma: